|

The images and accounts of Haiti’s devastation following

Hurricane Matthew’s passage on Oct. 4 are gut-wrenching.

The death toll is in the hundreds and continues to rise.

Entire villages in the country's southwest were

obliterated. The response of a Haitian government, left

besieged and without resources by decades of foreign

plunder, is anemic. The victims’ anguished appeals for

help are heart-rending. The United Nations now says 1.4

million people are in need of assistance, urgent and

immediate for half of them. Distressed onlookers around

the world want to do something, anything, and fast.

But the greatest

danger in the hurricane's aftermath may not come from

the destruction of crops and infrastructure, the

inevitable spike in cholera cases, or the sudden

homelessness of tens of thousands. It may come from the

aircraft carriers, foreign troops, food shipments, and

hordes of NGO workers which are now descending on Haiti

ostensibly to help the storm’s victims.

This supposed aid

may end up undermining local food production, sabotaging

pending elections, reinforcing the foreign military

intervention in the country, and generally subverting

Haiti’s recent moves to regain its sovereignty.

We saw this

scenario almost seven years ago, following the 7.0

earthquake that leveled the town of Léogâne and the

region around the capital city of Port-au-Prince on Jan.

12, 2010. In the days after the earthquake, the United

States deployed 22,000 troops to Haiti without the

permission of the national government, took over the

Port-au-Prince airport, and

militarized

the humanitarian response.

“Marines armed as

if they were going to war,” exclaimed the late

Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez in early 2010. “There

is not a shortage of guns there, my God. Doctors,

medicine, fuel, field hospitals, that is what the United

States should send. They are occupying Haiti in an

undercover manner.”

(That intervention

and much else about U.S. meddling in Haiti have been

detailed in a joint publishing project begun in 2011

between Wikileaks and

Haiti Liberté

weekly newspaper,

which partnered with

The Nation

magazine on many

English

language articles.)

Today, the U.S. has

sent the aircraft carrier USS George Washington and an

amphibious transport vessel, the Mesa Verde, with

300 Marines

on board, as well as

100 Marines

with nine helicopters from Honduras.

Richard Morse, who

runs Port-au-Prince’s iconic Oloffson Hotel, returned to

Haiti on Oct. 9 and tweeted: “Lots of U.S. military on

the plane.”

In contrast, the

day after the hurricane hit, Venezuela flew 20 tons of

humanitarian aid to Haiti – food, water, blankets,

sheets, and medicines. It dispatched two more shipments

in the following days, including a ship containing 660

tons of material that includes 450 tons of machinery to

remove debris and fix roads and bridges and 90 tons of

non-perishable foods and medicines, supplies, tents,

blankets, and drinking water. It has also dispatched 200

doctors, many of them Cuban-trained. All this despite

very difficult economic conditions in Venezuela as well

as a relentless political assault by Washington against

the Venezuelan government.

In this latest

disaster, “Venezuela was the first to help Haiti,” said

the Haitian Ambassador to Caracas, Lesly David.

Cuba, meanwhile,

has

supplemented

its revered 1,200-doctor

medical

mission to Haiti

with 38 personnel from the Henry Reeve International

Contingent of Physicians Specialized in Disaster

Situations and Serious Epidemics, which set up field

hospitals in Haiti in 2010 as well. As Washington sends

soldiers, Venezuela and Cuba send doctors.

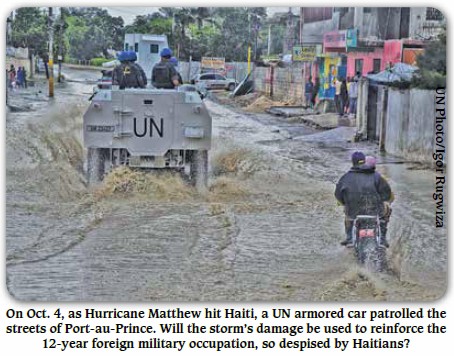

In the longer term,

it is likely that Washington will seek to use the

post-hurricane crisis to bolster its proxy force, the UN

Mission to Stabilize Haiti (MINUSTAH), which has

occupied Haiti in violation of Haitian and international

law for 12 years, following the overthrow of Haiti's

elected president on Feb. 29, 2004. (MINUSTAH was

expanded

from 7,000 to 11,500 soldiers and police officers after

the 2010 earthquake.)

MINUSTAH's mandate

expires on Oct. 15. In the face of Haitian and

international outcry and the withdrawal from the force

of several key Latin American nations – Argentina,

Uruguay and Chile – outgoing UN Secretary General Ban

Ki-moon

recommended

on Aug. 31

extending the mandate by only six months, less than the

customary one-year renewal. He says a “a strategic

assessment of the situation in Haiti” is needed.

However, Ban

conditioned this shorter mandate on the hope that “the

current electoral calendar will be maintained” so that a

“strategic assessment mission would be deployed to Haiti

after Feb. 7, 2017,” the date on which a new elected

president is supposed to be sworn in.

As a result of

Hurricane Matthew, it is now unlikely that an elected

president will be inaugurated on that date. Haiti’s

Provisional Electoral Council (CEP) has postponed

indefinitely the elections which were to take place on

Oct. 9, involving a re-do of a first-round presidential

vote (that of Oct. 25, 2015 was patently fraudulent) and

a run-off for several Haitian legislature seats.

The CEP is due to

announce on Oct. 12 the new electoral schedule. (Leaks

suggest it may propose Oct. 30, 2016.) It may prove

impossible to hold the postponed pollings in time for a

February presidential inauguration because tens of

thousands of would-be voters on Haiti’s southern

peninsula have surely lost their electoral cards while

many polling places – mostly schools – will need repairs

or complete rebuilding.

The potential

absence of an elected president in time for the

constitutionally-mandated inauguration date would surely

be used as an excuse for the extension of MINUSTAH’s

mandate, despite Haitians being almost unanimously

opposed to the troops’ presence. The MINUSTAH, now

numbering 5,000 soldiers and police officers, is reviled

due to its massacres, murders, rapes, and other crimes

against Haitians, but mostly because its Nepalese

contingent introduced cholera into Haiti in October

2010.

Nearly 10,000

Haitians have died from cholera and more than one

million have been infected. The UN has fiercely resisted

any culpability for the cholera disaster.

The disease spreads

when cholera-infected sewage mixes with drinking and

washing water, a situation which arises more easily when

there is massive flooding, as after Matthew.

As for the

relationship between post-hurricane rebuilding and the

upcoming elections, the earthquake’s aftermath is

instructive. Then-U.S. Secretary of State Hillary

Clinton and former President Bill Clinton

took command

of Haiti’s post-earthquake reconstruction through the

Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC), sidelining the

Haitian government and Haitian President René Préval.

The resentful Préval became something of a figurehead,

with the Clintons and their coterie running the show.

The powers behind

MINUSTAH – the U.S., France, and Canada – intervened

aggressively following the 2010 earthquake to install a

pliant president. As Préval's electoral mandate was

finishing, his party’s successor candidate, Jude

Célestin, finished the first-round presidential vote in

November 2010 in second place. But Washington

intervened, led by Secretary of State Clinton, and

replaced Célestin with the third place finisher, Michel

Martelly, a ribald musical performer of the political

extreme-right. He went on to win the March 2011 run-off

vote.

Could a similar

power-play take place in Haiti’s next election,

especially with the likely election in November of

Hillary Clinton as the next U.S. president?

Then there is the

question of emergency aid – food, water, shelter, and

medical supplies. There is an obvious need for all of this in

the immediate term, such as that sent by Venezuela.

However, in the past, Washington has used its food aid

to crush and debilitate local Haitian food production.

Former CARE employee and Haiti-resident researcher Tim

Schwartz documented this at length in his book

Travesty in Haiti: A True

Account of Christian Missions, Orphanages, Fraud, Food

Aid and Drug Trafficking.

He wrote that the role of food aid “was not principally

to help people but to promote overseas sales of U.S.

agricultural produce. The consequences have been

devastating throughout the world.” That aid, he argued,

brought ruin to small Haitian farmers.

“Westerners wanting

to help shouldn’t assume that there are no resources

available to Haitians in country,” writes Haitian

Jocelyn McCalla in

The Guardian

on Oct. 6.

“While charitable goods may provide temporary relief,

they can hinder recovery in the long run to the extent

that they can have a negative impact on the local

economy.”

In 2010, most of

the humanitarian disaster aid was funneled through

international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) and

the result was disastrous. Even the Clintons’ own

daughter, Chelsea, was “profoundly disturbed” by what

she saw on the ground. She wrote in

a

declassified email

in early 2010 that the “incompetence is mind numbing,”

that “Haitians want to help themselves and want the

international community to help them help themselves,”

and that “there is NO accountability in the UN system or

international humanitarian system (including for/ among

INGOs).”

The current Haitian

government, headed by interim President Jocelerme

Privert, is trying to take control of the disaster

relief efforts and funds. Following the earthquake, only

one per cent of aid funds went to Haitian authorities.

This time, the president’s office has reinforced the

Permanent

National Office for Risk and Disaster Relief

(SNGRD) through which all national and international

disaster relief is to be channeled and coordinated. What

will be Washington’s response to this initiative?

The U.S. was

angered earlier this year when the Privert government

resisted its pressure not to form an independent

verification commission to investigate the fraud-plagued

Aug. 9 and Oct. 25, 2015 elections. Anger became outrage

when Privert’s CEP respectedthe

verification commission’s recommendation to redo the

2015 presidential first-round, and Washington and the

European Union said they would withhold all financial

support. Commendably, cash-strapped Haiti was undeterred

and has managed to fund the elections by itself.

Haitian government

leadership of the relief efforts should begin with its

being able to establish the death toll. The Haitian

government and foreign media are differing over how many

people have died from Hurricane Matthew. As of this

writing, the international media is saying that more

than 900 people perished, while the Haitian government’s

Civil Protection Directorate (DPC) gives an official

nationwide count of 372 dead, four missing, 246 injured,

and 175,509 persons housed in 224 temporary shelters.

Writing on Oct. 8,

Haitian journalist Dady Chery

has reported,

“Once the United States military and journalists began

to assess the hurricane’s damage by some counting system

of their own invention, the number of Haitian casualties

skyrocketed, and there were no longer any reports of how

the dead met their fates. Indeed, the number of the

Haitian dead from Hurricane Matthew has doubled

approximately every 12 hours since Tuesday [Oct. 4]

morning and is now estimated to be 800.”

The higher

“casualty counts should be examined carefully and with

great skepticism,” Chery continues. “For one, there no

longer appears to be a distinction between the missing

and the dead. For example, the children from a collapsed

orphanage are presumed to have died, but no evidence of

their deaths has been offered.”

“It is in the

interest of the occupying powers to pressure Haiti to

exaggerate the human and material costs of the

hurricane,” Chery concludes.

Indeed, Washington

will likely use this latest Haitian crisis to further

its own economic and political agenda and to bully and

undercut President Privert, who has shown some temerity

and independence since his interim appointment by

redoing the 2015 presidential election in the face of

fierce opposition from Washington, Ottawa, and Paris.

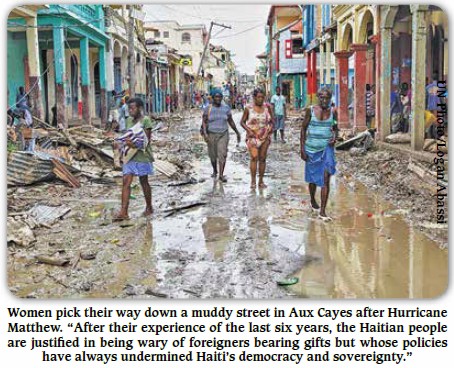

After their experience of the last six years, the

Haitian people are justified in being wary of foreigners

bearing gifts but whose policies have always undermined

Haiti's democracy and sovereignty.

“If people are

concerned about the long-term sovereignty and capacity

of the country of Haiti to develop its own resources, I

would recommend against the large charities, which in my

view just perpetuate the conditions of poverty and of

political instability that cause the country to be so

vulnerable in the first place,” Roger Annis of the

Canada Haiti Action Network (CHAN) told the Globe & Mail

on Oct. 9.

International aid

by whatever agency able to deliver it is being welcomed

by Hurricane Matthew’s Haitian victims and their

government. But the lesson of the 2010 earthquake is

that aid and reconstruction must be directed by Haitians

and for Haitians. Otherwise, this latest disaster will

only aggravate the long disaster of big-power

intervention into the country. That, not inevitable

storms and earthquakes, is the largest obstacle facing

Haiti in its struggle for development and sovereignty.

(Readers

are encouraged to contact local Haitian consulates or

embassies to find out how to contribute directly to the

Haitian government or its affiliated agencies.)

Roger Annis contributed to this article, which is also

published on

CounterPunch. For

background to the long history of foreign interference

in Haiti, read 'Haiti’s

humanitarian crisis: Rooted in history of military coups

and occupations', by Kim Ives and

Roger Annis, May 2011. For an assessment of 2010

earthquake aid five years on, read, 'Haiti's

promised rebuilding unrealized as Haitians challenge

authoritarian rule,’ by Roger Annis

and Travis Ross, Jan 12, 2015. The website project 'Haiti

Relief and Reconstruction Watch'

documents Haiti's difficult experiences following the

January 2010 earthquake.

|