|

Caribbean art has attracted increasing

attention as evidenced by sizable museum exhibitions devoted to

it in the past few years. The art’s aesthetic underpinning is

the product of multiple, stratified societies that are still

more or less negotiating, in diverse ways, their political and

socio-cultural identities, so it’s hard to capture in a single

show. Furthermore, some of the work is produced by expatriate

artists who still maintain strong ties to their birthplace. Yet,

“Caribbean Cream: What You See Is What You Do,” an

exhibition at a new Jersey City gallery, BrutEdge, directed by

Gail Granowitz and Reynald Lally, offers a satisfying take on a

fundamental concern of the region’s artists.

Curated by Lally with the

assistance of Jorge Alberto Perez, who also handsomely designed

the show, “Caribbean Cream” includes 14 artists from

Haiti, Jamaica, Cuba, and Barbados. It’s not intended as a

survey. The impetus for it, we’re told, is based on the Haitian

saying sa ou fè, se li ou wè (“what you do is what you

see”). The objective certitude implied in this saying points to

the fact that, contextually, the locus of identity can be found

in the transformative act of conceptualizing the past as it

relates to the present. Yet, we are further informed that the

show is an attempt simply to explore the “tensions” between a

Caribbean that is empirically defined versus one that is

historically complex, hybridized, and, it would seem,

indeterminate.

Fortunately, the

works presented in the show do justice to the pithy Haitian

saying, superseding the would-be aesthetic and historical

indeterminacy of Caribbean art. For instance, Lally, who for

years ran the Bourbon-Lally Gallery in Haiti and then in Canada,

doesn’t altogether set aside the raw, fantastical aspects of the

types of art he has long championed in order to shoehorn the

show into the hip contemporariness associated with such

object-free mediums as film and video, deadpan ironic

photographs, and puzzling over-the-top installations. This was,

to a considerable extent, the case with the Brooklyn Museum’s

exposition “Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art.”

Tellingly, BrutEdge gives prime

wall space to Myrlande Constant’s “Anacaona,” a large,

arrestingly colorful sequined piece replete with flowery vines,

figures in grass skirts with spear or scepter in hand, and

feathers in their hair. The work flaunts its (faux) primitif

lineage. And unlike the three-museum survey, “Caribbean:

Crossroads of the World,” the BrutEdge exhibition does not

deploy its energy deep into the meandering recesses of the past

only to conjure up an art that’s aesthetically diffuse and

unassertive or a Caribbean that’s tethered to the all so nuanced

interpretations of the forces of history. Shunning postmodern

irony altogether, the works Lally has gathered posit a bracingly

affirmative identity with (as well as a self-directed

transformation of) the local and the regional.

The assertion of a locus for a

Caribbean identity that’s in the process of transformation and

construction is foregrounded in various ways in most of the

works in the show. One would expect, for instance, Mario

Benjamin’s “Cannibal Flowers,” a large painting predating

Haiti’s 2010 earthquake that shows an assortment of leaves

seemingly stenciled in an all-over format on a neon-like

chartreuse background, to be merely an evocation of lush

tropical foliage or of an exotically charged paradise. Instead,

the wafting, dusky leaves come across as if they had been

X-rayed and, in the process, incinerated. To complicate

matters, here and there the artist messily, listlessly smears

certain passages, suggesting in a couple of spots vestiges of

owlish eyes. So the painting is tantamount to a vision in which

Benjamin attempts to will a balancing out of the abjectness as

well as the potentialities of his subject. Here, the identity of

self and object together with the symbolic possibility of

transforming this fusion points to the dynamics of a Caribbean

identity in the making.

A number of other artists

project this transformative potential in their contribution,

including Vladimir Cybil Charlier, whose elliptical works

combine images, ink drawing, and beaded passages on background

photographs of cracked or leveled buildings from Haiti’s

earthquake.

Ebony Patterson’s “Disciple

VI,” from her “Gangstas for Life” series, transforms

a skin-bleached, androgynous portrait of a presumed Jamaican

hipster into an iconic saint. The artist achieves this

transformation by infusing signs of social deviance or otherness

in her subject: there’s the sitter’s rakishly turned,

glitter-covered baseball cap, the flame-like jungle brush or

mountain range behind his shoulders, the red-loud lipstick on

prominent lips that contrast sharply with a ghostly, mask-like

face, the stylish bandana which could have doubled as

concealment for the face. Patterson then conflates all of this

with old-world tropes of salvation in the forms of a lacy,

heavenly halo and a dangling cross.

If Patterson integrates the

ostensibly fraught composite aspects of her subject into a new

model of (Jamaican) blackness, Olivia McGilchrist takes a

somewhat different tack. As stated on a wall label, she is a

white-complexioned, Jamaican-born artist who grew up and was

educated in France and England but now resides in her birthplace

since her “sudden return” there. She insists on presenting the

personas in her small video stills as unambiguously racialized.

In “Bay,” from her Whitey series, we see a white-masked

female standing on the stern of a boat that’s anchored to a

beach. She looms as if she were a bugbear in her viewers’

imagination. So race is something that’s performed, McGilchrist

suggests. It’s a category that’s imposed. Among her other six

exquisite film stills (from her Native Girl series), we get the

reverse of “Whitey.” Here, the artist confronts us with

the theatrically staged presence of a primordially masked female

in presumably African garb who, from mostly pitch-black

surroundings, seems to insist on the viewer seeing and accepting

her as an alluring powerful other.

It would seem that the locus of

Caribbean identity thus far is to be found somewhere in the

vicinity of the racialized (as well as gendered) poles

established at least since colonial slavery days, although it’s

not specifically determined or mapped out. This is born out by

other works in the show, including those of Dionne Simpson and

Florine Démosthène. It’s especially evident in the crisply

delineated lithographs of Jocelyne Gardner, who is known for her

depictions of meticulously coiffed black heads of hair seen from

the back. But in a sense, her prints are not about heads of hair

at all. With their schematic artificiality, the braids and

strands of hair are tantamount to metaphorical encodings that

Gardner gropes through so as to fathom the topography of

colonial oppression and racism. Like the stills of McGilchrist,

Gardner’s headless hair styles, along with the instruments of

restraint and torture that complements them, are woven tales —

tropes that cry with burning desire to reconcile disquieting,

painful feelings and memories with the neocolonial present.

Though shorn of the politics of

colonial memory, the works of two other artists in the

exhibition, Carlos Estevez and Pavel Acosta, are quite pertinent

here. They suggest that the aesthetic means of reconciliation

itself—that is, the conceptual exploration of the tension

between the present and the past, mind and memory, or what is

versus what we think exists — is at the root of Caribbean

identity. With their backgrounds prettily dabbed with warm

washes of paint, Estevez’s two paintings come across as fluffy

as well as quirky and quaint in that they smack of some familiar

dada pieces by Francis Picabia or of the cartoony visions

of Paul Klee. Yet, somewhat like the technical rigamarole or

aesthetic rituals of Dionne Simpson, Estevez introduces into his

paintings countless obsessively interconnected details worthy of

a maniacal outsider artist. Such details project symbolically

the rational mechanics of the sexual attraction and transaction

unfolding between the male-female couple in his two paintings.

Through the act of elucidating the heterosexual pull between his

figures, Estevez exemplifies the identity of his rational

approach to his memory or subjective visions. The past is thus

subsumed into the act of painting—which stands for the present.

Ultimately, that Caribbean

identity is not so indeterminate and freighted by the sheer

multiplicity of past historical truths and possibilities that

are in turn compounded by present memory is succinctly

exemplified in the contribution of Pavel Acosta. His approach

perfectly suits and affirms the notion of a definite locus for

Caribbean identity. The artist uses in his art a “recycled

paint” technique, wherein he cuts up discrete layers of paint

and then collages them like bits and strips of paper onto

canvas, to create his patchy representational images.

If his technique in “Marina”

seems a bit flat-footed, it’s perhaps partly because Acosta is

suggesting in the work that, like his horizontally split sailing

ship whose two halves simultaneously occupy the upper and bottom

edges of the picture, he is trying to constrict the span of time

into the spatial dimension of his canvas. And if the artist

transforms time into space, of course he can no longer return to

or revisit the past. So just as his technique makes his works

look as if he applies his paint clippings strictly from the

picture plane outward, Acosta draws the past into the present

and ultimately toward the viewer or himself.

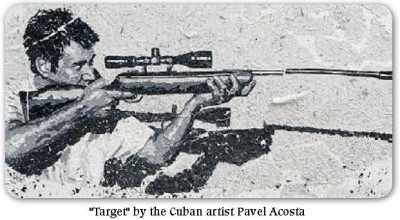

This is exceedingly clear in

his solidly implemented “Target.” Here, Acosta’s

deceptively banal, pop art-like image of a man aiming a rifle

across the field of the canvas is metaphorically an exercise in

self-identification, not so much marksmanship or violence. For

the barrel of the shotgun, given the piecemeal technique, is

misaligned, and the target that the shooter is aiming at is not

objectified. Nevertheless, the image’s heavy shadow intimates

that the shooter’s target might be himself—his own identity.

Indeed, the gun’s muzzle rests on the picture’s right edge,

suggesting that its discharge would hit the shooter himself in

his upper right arm, which, cleverly, Acosta conspicuously

extends beyond the picture’s left edge. All in all, through his

pictures’ symbolic space, the artist dispenses with the

dimension of time by transposing the present and the past into

himself—an act that parallels the self-object fusion and

potential transformation that Benjamin attains in his “Cannibal

Flowers.”

So if it’s not exactly

demarcated, the locus of Caribbean identity is not to be found

solely in the historical past or even in memory. It’s also an

aesthetic and conceptual identity reached through the

transformative acts that the region’s scattered artists elicit

from themselves in a definite present.

“Caribbean Cream”

September 29th- November 23rd

, 2013

BrutEdge Gallery, Space # 574

Mana Contemporary

888 Newark Ave., Jersey City, NJ 07306

Tel: 646 233-1260

Info@brutedge.com |