|

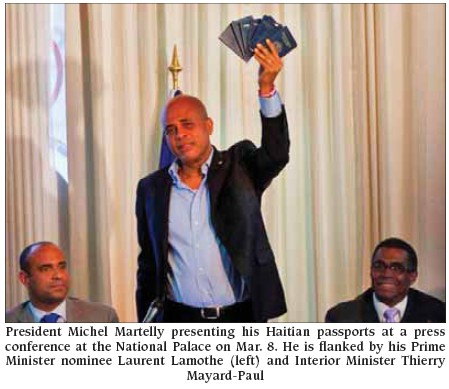

“With the permission that

the President has just given me, I can inform you that President

Martelly is not American, he is Haitian.”

Thus spoke U.S. Ambassador

to Haiti Kenneth Merten at Haiti’s National Palace during a Mar.

8 press conference which was supposed to lay to rest persistent

charges that President Joseph Michel Martelly holds or held U.S.

citizenship.

If the charge proves true,

“double nationality” would disqualify him from holding office

because the Haitian Constitution requires presidential

candidates to have “never” renounced their Haitian

citizenship.

The problem is that Ambassador

Merten only used the present tense, not eliminating the

possibility that Martelly may have been a U.S. citizen at some

point in the past, say members of Haiti’s Special Senate

Commission investigating the charges of double nationality

against Martelly and 38 other high government officials.

“We haven’t asked about that

yet, but we will,” said Sen. Moïse Jean-Charles, who heads

the Senate Commission now examining the eight Haitian passports,

spanning the years from 1981 to the present, which Martelly

presented at the press conference.

Haïti Liberté spoke by

telephone to U.S. State Department officials in Washington,

seeking clarification of Ambassador Merten’s statement and

whether Martelly has ever held U.S. citizenship. They refused to

speak on the record and pointed to Ambassador Merten’s statement

as the State Department’s “final word” on the subject.

“I can also add that I was

with him [President Martelly] and the First Lady when he

surrendered his [U.S.] residency card, when he handed it to the

Consulate and we gave him a visa,” Merten continued.

Ironically, this revelation

raised new concerns that Martelly may have lied to election

authorities about whether he was compliant with the

Constitution’s requirement that presidential candidates reside

in Haiti for five years prior to running for office.

“How can you meet the

residency requirement to run for President in Haiti when you

meet the requirements to be a U.S. resident and hold a valid

U.S. green card?” asked Sen. Moïse. “ You can't have it

both ways.”

Martelly’s holding of a U.S.

residency card would seem to preclude the possibility that he

was a U.S. citizen. However, Sen. Moïse and his colleagues have

discovered numerous irregularities with the passports that

President Martelly presented to the press, keeping alive

questions about possible double nationality.

“We see stamps [in the

Haitian passports] showing that he left Haiti, but we don’t see

stamps [in them] for where he went,” Sen. Moïse told

Haïti Liberté. “Then, from 2004 to 2007, he never

traveled, he never came to Haiti [according to Haitian

Immigration records], while we see a lot of Haitian

stamps [in the passports]. They stamped them, but they didn’t

even sign them. There’s about a dozen fake stamps.”

Sen. Moïse also charged that “there

are passports which don’t have visas. If you have a passport

which is in the name of Michel Martelly which doesn’t have a

visa in it, you’d have to have a residency card or a U.S.

passport to enter the United States. But he gave us a passport

which didn’t have either of these things.”

There are also contradictions

with some U.S. documents listing the president’s name as Michael

Joseph Martelly, rather than Joseph Michel Martelly, Moïse said.

The mystery was deepened by a

trip which Martelly made from Haiti to Miami on Nov. 21, 2007, a

journey which Sen. Annick Joseph had revealed last week. The

Senate Commission had been told by several people it interviewed

that Michel Martelly was on an American Airlines flight that

day.

“The President sent [the

executive’s liaison in charge of relations with the Parliament,

Ralph Ricardo] Theano to us, and he swore that on Nov. 21, 2007

he was at a seasonal celebration (fèt chanpèt) with President

Martelly who was performing [his konpa music act] in Haiti, that

the president did not travel,” Sen. Moïse said. “We went

to immigration, they gave us all the travel manifests for every

single flight which traveled that day, and they told us the

president did not travel. Everybody around the president said

no, he didn’t travel.... Then the president himself shows at the

press conference a passport with a Haitian stamp indicating that

yes, he did travel on Nov. 21 [2007]. Now the Immigration

Director is saying that he has to find the person who put that

stamp.”

The passport in question also

appears to have a U.S. entry stamp on Nov. 21, 2007 but Moïse is

suspicious. “I do not believe it is authentic,” he said.

The Senate Commission is also

perplexed by and looking into a passport that was apparently

issued to Martelly in 1981 and expired in 1993, a duration of 13

years. Most Haitian passports have a maximum duration of five

years.

Furthermore, the Immigration

department has records of issuing only four passports to

Martelly over the years, not the eight he presented, the

commission says.

According to Sen. Moïse,

President Martelly never intended to turn over to the Senate

Commission the passports brandished at the Mar. 8 press

conference. For months, he had defied the Senate Commission,

saying it had no authority to demand his passports, which would

remain, as he said in one press conference, “in the

President’s pocket.”

But Martelly’s intransigence

began to create the public perception that he was hiding

something, and finally a delegation of “Religious Leaders for

Peace” convinced him to make public his passports and break the

stand-off. The delegation, which sat around him at the press

conference included the Catholic Bishop of Nippes, Pierre André

Dumas, the Rev. Sylvain Exantus of Haiti’s Protestant

Federation, Bishop Jean Zaché Duracin, the head of the Episcopal

Church, mambo (vodou priestess) Evoie Auguste representing the

Vodou sector, and the Rev. Clément Joseph of the Mission of

Churches in Haiti.

But President Martelly had only

wanted to make a “media show” with the passports, not

turn them over to the Senate Commission, according to Sen. Moïse.

“I am giving these to you

for verification, but you cannot walk away with them,”

Martelly said when giving the passports to Bishop Dumas.

“But Pastor Exantus said

that they could not invite him to something to use him for a

mascarade, and it was the pastor who brought the passports to

us,” on Mar. 9, said Moïse.

At the time of the press

conference, three senators allied to Martelly resigned from the

investigating commission: Joseph Lambert, Youri Latortue and Yvon Buissereth. Lambert and Latortue charged that the

commission, which they had led for several weeks, was part of a

“destabilization campaign” and that there was “no

evidence” to support the U.S. citizenship questions swirling

around Martelly.

Senate President Dieuseul Simon Desras had said that

Martelly’s passports would be returned on Mar. 12, but Sen.

Moïse now says that the Commission’s senators will be holding

onto the passports “indefinitely” until they get answers

to their questions about them. |