|

During the first week in

October, I took part in a human rights delegation to Haiti led

by the U.S. grassroots organization School of the Americas (SOA) Watch. The delegation

of 17 activists from around the U.S. wanted to gain firsthand

knowledge about the UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH),

a military occupation force of 13,000 troops and police. We also

saw numerous initiatives being organized by Haitians to promote

their nation’s dignity and sovereignty.

SOA Watch monitors and protests

the activities of the U.S. Army’s School of the Americas (SOA),

based at Ft. Benning, Georgia, where the officers of repressive

Latin American military and police forces, including Haiti’s,

are trained. (In January 2001, the school was renamed the

Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation.) I work

in the Washington, DC office of SOA Watch, which carries out its

work through vigils and fasts, demonstrations and nonviolent

protest, as well as media and legislative work.

The conversations and

encounters that I had on this delegation to Haiti have inspired

me and touched my heart, changing my perspective on the world.

While I do not represent the whole delegation or even SOA Watch,

I would like to share some reflections about the numerous

meetings we had and things we witnessed.

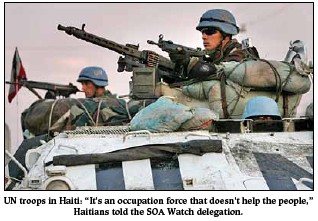

We observed MINUSTAH armored vehicles,

soldiers and police patrolling every corner of Port-au-Prince,

where Haitians eke out basic survival amidst earthquake rubble.

The UN Security Council

deployed MINUSTAH in June 2004 to replace the U.S., French

and Canadian troops which occupied Haiti following the coup

d’état (supported by those same nations) against former

President Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

According to its mandate, MINUSTAH should focus on training and strengthening the Haitian

National Police. But, in reality, we observed that MINUSTAH is

primarily a military mission which provides security, not for

Haiti’s people, but rather for foreign companies (including most

of the large NGOs) and Haiti’s business elite.

“It's an occupation force

that doesn't help the people,” a representative from the

“Grassroots Coalition against MINUSTAH” told us. “They

terrorize the people in the poor neighborhoods, they say they

are here to help the people of Haiti who are in misery, and

their sole objective is to support the multinationals and the

bourgeoisie in Haiti.”

Our delegation learned how

militarization is often justified as providing security for

humanitarian assistance. For example, 22,000 U.S. troops and an

additional 4,000 UN troops were deployed to Haiti following the

Jan. 12, 2010 earthquake. But other than a few token efforts,

those troops did not generally help to save lives, remove

rubble, or rebuild homes. They primarily patrolled streets and

guarded businesses, supposedly to prevent “looting.”

The UN troops, we were told,

have often conducted deadly raids in Haitian shantytowns and

against anti-coup demonstrations. In short, MINUSTAH

represses the very people it pretends to protect.

Although some people feared

that security might degenerate if MINUSTAH leaves, the vast

majority of Haitian grassroots groups agreed that MINUSTAH is

causing more harm than good.

The UN spends $2 million a day

to deploy MINUSTAH in Haiti, while hundreds of thousands of

Haitian earthquake victims remain homeless and destitute.

We heard about cases where

Haitians had been sexually abused by MINUSTAH troops and how

others had contracted cholera, a now epidemic disease which

Nepalese UN soldiers brought to Haiti one year ago. Cholera has

now killed over 6,500 Haitians and sickened over 420,000.

“The police and MINUSTAH

don’t come out at night,” said one woman out of several who

had been victim of sexual violence in the tent camps. Her

statement was quickly affirmed by many nodding heads in the

meeting we held with several women’s organizations. It became

clear to me through many conversations like these that MINUSTAH

troops do not protect women from rape or stop other crimes. On

the contrary, we heard testimony of how UN soldiers had

committed rape and other sexual violence.

We also heard testimony that

MINUSTAH troops have aided in the illegal evictions of tent city

residents, violently repressed demonstrations, and attacked some

of Haiti’s poorest communities. Far from a neutral party, the UN

took the side of the coup-produced government from 2004 to 2006,

aiding in the repression of the Lavalas Family, Haiti’s largest

political party, and in maintaining that party’s leader,

Aristide, in exile. This constitutes repression of Haitian

sovereignty, not democracy promotion.

Even the legality of MINUSTAH’s

mandate is questionable, we learned from Haitian lawyers. Haiti

has no civil war and is no threat to international peace and

security. Furthermore, under an agreement signed by Haiti’s

illegal coup government and the UN, MINUSTAH troops cannot be

tried in Haitian courts for violations of human rights.

However, UN troops have

routinely violated Haitian’s human rights. We visited Cité

Soleil and were shown the thousands of bullet holes that still

pockmark buildings following massacres carried out by MINUSTAH

troops from 2005 until 2007.

We were told the story of a

young man in Cap Haïtien who was found hanging from a tree after

the alleged mistress of a MINUSTAH commander falsely accused him

of stealing money; the day after his death, she found her

misplaced purse. When a Haitian judge tried to look into the

case, the UN brass blocked the investigation.

MINUSTAH’s “presence helps

perpetuate their staying,” one woman told us. “They

should leave because they are wasting resources and not fixing

anything. MINUSTAH money should instead train more police and

security forces, and go to creating more jobs.” The

overwhelming message we received: MINUSTAH is in Haiti to

maintain the status quo, which features a huge chasm between

between rich and poor.

SOA Watch helped initiate a

recent letter to Latin American goverments, signed by a number

of prominent Latin American intellectuals, academics and human

rights defenders, demanding MINUSTAH’s immediate withdrawal.

Also, our delegation released

the following statement: “Members of U.S.-based human rights,

legal, faith-based, and policy organizations call for an end to

foreign intervention in Haiti today, including the withdrawal of

the UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti, MINUSTAH.”

Many Haitians we spoke to were

also concerned that the current President Michel Martelly wants

to bring back the Haitian army, which Aristide dismantled in

1995. The former Haitian army, which was set up by the U.S.

Marines following their 1915-1934 military occupation, was a

corrupt and brutal force, responsible for many coups and

massacres. It never protected Haiti against foreign states; it

only repressed and terrorized the Haitian people.

The new force that Martelly

proposes would cost $95 million annually to start. This is money

Haiti cannot afford, for a force the Haitan people do not want

or need, people told us.

Haitians we spoke with also

denounced NGOs that purport to “help the people” but

which are, in their view, corrupt and parasitical. The NGOs

spend more on overhead and living expense than they do on

providing aid. Many of these same NGOs participated in the coup

against President Aristide by financing the opposition and

writing reports filled with disinformation that contributed to a

pro-coup media campaign. Many of these NGOs also support the

neoliberal agenda which is destabilizing democracy in Haiti.

Haitians provided great

inspiration for continuing our social justice work and

organizing here in the U.S.. Their history is inspirational: the

only successful slave revolution routed the most powerful army

at the time, and then, as a free nation, provided support and

safe refuge for anyone fighting slavery and colonialism,

including Simon Bolivar, who led the freedom struggles on the

South American continent.

This heroic history has

instilled a resilience in Haitians that you can see in the faces

of women as they balance huge baskets on their heads, or in the

faces of children playing soccer in the dust of Cité Soleil.

Despite their near total lack

of financial support, many Haitian grassroots organizations

continue fighting, interacting and empowering the poorest and

most disenfranchised sectors of Haitian society in the pursuit

of jobs, water, food, housing, and security. One representative

of MOLEGHAF (Movement for Liberty and Equality by Haitians for

Fraternity) told us that “there cannot be freedom if people’s

basic needs for survival are not respected and met.” Others

whom we interviewed repeated this several times during our

visit.

No amount of studying or

analysis beforehand can prepare you for the situation in Haiti.

My conclusions after this, my first trip to Haiti, are clear and

straightforward: I support Haitians’ demand for sovereignty and

believe they have the right to govern themselves. We must

support lawyers working both to bring justice for crimes of the

past but also to empower people to change their own futures. We

must support student groups working for justice and reparations

for victims of MINUSTAH violence and cholera. We must support

Haitian journalists working to investigate injustice and give

voice to the Haitian people’s concerns. We must support Haitian

women's organizations working on issues of rape and gender

imbalance. I support the demands from all quarters for “solidarity,

not a military force,” solidarity like the doctors provided

by Cuba and the petroleum provided by Venezuela. I hope that

people from the international grassroots community will join in

the call that international money raised for Haiti be spent on

Haitian initiatives to benefit the Haitian people, and not on

military occupation and economic initiatives that benefit the

international and Haitian ruling elite.

I have learned how the U.S.

government has worked to undermine rather than to build

democracy in Haiti. The strategies to solve these problems are

complicated and not mine to determine. But I will continue to

support the organizations working with the Haitian people for

democracy, justice and sovereignty.

Becca Polk works at SOA Watch in

Washington, DC and can be reached at

Becca@soaw.org. |